Tens, maybe hundreds of thousands of pages have been written about the horrors of the Nazi party’s concentration camps. I feel like adding words to the tens of millions already written is a waste of your time. But I must write them anyway.

I extended my business trip to Munich by a day, just so I would have the opportunity to walk around and enjoy the city without worrying about keeping up with a group. Alone, I am the slowest walker I know, and the ever-efficient Germans pass me often, apologizing with an entschuldigung as they pass. I can make a kilometer last an hour, and I often do.

The first order of business was to go to Dachau concentration camp. It was something that I wasn’t wanting to do, in some sense, but I felt an obligation to go, being so close, and never having seen a prison camp, it was my duty.

The S-bahn ride through the outskirts of Munich was uneventful. We passed suburbs, looking like most suburbs, but cleaner and better planned. Gotta love the Germans. Then it was announced…Dachau Station. Please exit on the left.

I exited into a quaint little village. There were the usual near-the-station tacky food stands (“Englisch Menu!”) but walking a few hundred meters in any direction revealed a lovely town, most likely a bedroom community of Munich, 40 minutes away by train.

I jumped on a bus to catch a ride to the actual site, a national historical site. If the Germans are ashamed of their past, you wouldn’t know from this. There is a sense that the Germans are trying to educate. I was the only one there who wasn’t from a giggly middle school group, and I timed it so that I was always between groups. My plan worked perfectly.

Dachau was the first concentration camp, and it has a terrifying back story. Six weeks before Dachau opened, the Nazi leadership suspended parts of the German constitution, namely:

“Articles 114, 115, 117, 118, 123, 124 and 153 of the Constitution are invalid until further notice. Restrictions on the freedom of the individual, the right to free speech, including freedom of the press and the right of assembly and the right to form groups, infringements on the secrecy of post, telegraph and telephone communications, house searches, confiscation and limitation in property ownership over and above the previously legally specified limitations are now permissible.”

Sounds a lot like the Patriot Act, doesn’t it?

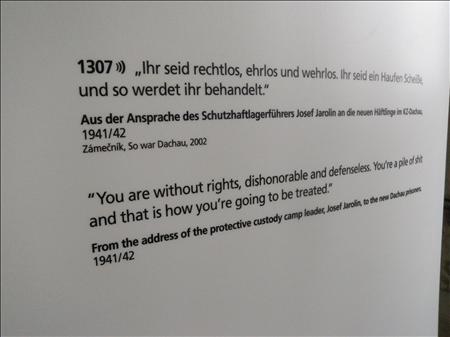

Dachau was obviously under construction, probably almost finished, so there was no doubt suspension of the constitution was already in the plan. Dachau first contained about 2000 inmates, a prison for political enemies, Communists, and other miscreants. It was insisted that this was “protective custody,” an Orwellian euphemism that makes your skin crawl.

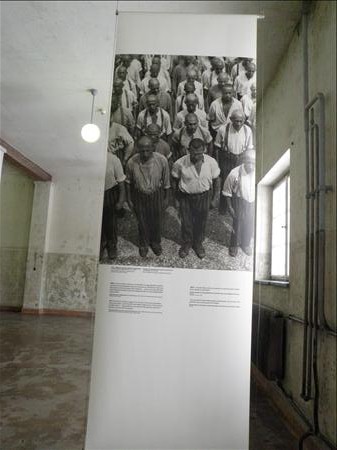

After walking through the main entrance, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI sign integrated into the gates, you turn right into the main buildings, now a museum. There, in excruciating detail, the history behind the camp and its many inmates is laid out in great detail. The idea was to show the people who were there…the individuals.

The scale of death and suffering was so great it makes your brain shut down and lump all those senseless deaths together in one, big tragedy. But making it personal…showing a man eating a picnic with his wife and kids in one picture, and showing another of the same man, head shaved and half his weight from the first picture…brings it home in a way that is staggering. That family having a picnic could be my own. That’s the intent.

The bunker held about 140 prisoners, mostly people who were considered more dangerous or instigators or someone some guard didn’t like. It was capricious and arbitrary. Punishment was sadistic and brutal. Many of the guards were casualties of the front lines and were retired to work at concentration camps. My guess is quite a few of them were deranged.

I have several pictures of gas chambers and the cremation building (Barrack Ten). I don’t want to put them up here. I spent ten minutes sitting in a gas chamber, pondering what an individual thought as they entered that 20 x 20 room with the low ceiling and fake shower heads. I spent about five minutes sitting in the corner of the crematorium, wondering what the people loading the bodies into the ovens thought about what they were doing…if it bothered them…if they went home to a wife and family…if they went to church Sunday morning and prayed for forgiveness. I don’t know. As I sat there in those rooms, the thought that came to me over and over again was “All is blackness and evil.”

In July 1961, Stanley Milgram, a Yale psychologist, created an experiment to determine how so many people could become so callous, unfeeling and brutal. This was during Adolf Eichmann’s war crimes trial in Jerusalem, and Milgram, a Jew, was curious about the relationship between authority and compliance to obey, even when the task was odious and inhumane. Milgram was searching for a mechanism to see what made the Germans so compliant to authority. But he had to test it here in the States.

What happened shocked Milgram. He had no need to take his experiment on the road. People from all walks of life, from graduate students to working class folks from New Haven, Connecticut had no problems administering what they thought were 450 volt electric shocks to a subject in the next room because a man in a white lab coat said “It is absolutely essential that you continue.” In fact, 65% of participants had no problem administering the highest shock. Zimbardo’s prison experiment at Stanford was no less frightening. Think Abu Ghraib with upper middle-class college students. It really happened.

Before we get on our high horses and blame Germans for being so [insert negative adjective here], we’re not exactly lily-white ourselves. What I learned at Dachau is that it could happen anywhere. All you need is a group of people who are perceived as a threat (Jews, gypsies, Communists, people named Mohammed), another group of people who are threatened, and a leader who wants to exploit both groups. There are days I wonder when we’re going to re-open Manzanar and fill it with Muslim-Americans (of course, for their own protection).

What I came away with is a sense of what can happen when people do nothing. I understand why they didn’t do anything…even the ones who tried to help by throwing a loaf of bread over the fence were unceremoniously tossed in the same camp: they were obviously subversive types.

On the train home, I made a promise to myself that I would do what I can to make sure it doesn’t happen here. But I don’t know what that means. Let’s say I’m living a quiet life as a shopkeeper in Dachau in 1944. I decide these poor prisoners could use some food, so I toss a load of bread over the fence. The next day a couple of thugs come into my shop and say, “Hey, Commie-lover, do that again and your wife and kids are taking a one-way trip to Barrack Ten.”

So what would you do?

It was a long train ride home.

Respectfully submitted,

Canoelover

This brought tears to my eyes. Thank you for the insight and sharing such a personal experience with us. I shall think through this in my yoga practice tonight. Honestly, I will be thinking on this for quite awhile.

Wow! Very powerful experience!!!

Canoelover.

Thanks for this poignant reflection. I had a similar moment when I was studying Latin American history as a student on the Augustana-in-Cuba program. As a part of the course we were required to read “The House of the Spirits” by Isabelle Allende. I had never read anything on Latin America before and coming to the end of the book I asked my roommate, a LA studies major, whether the book was true. Allende speaks of The Poet and The President, and her use of capitalization tipped me off to a real-life connection. My roommate sat aghast. “You don’t know?” she said.

The moment we can connect to the truth of a situation, we become a part of it. We are implicated in violence we watch and do nothing about. We are victims of the violence as we fear its effects on our own lives. When we are in the middle of these tragic moments in history that keep cycling into existence, whether in Germany, Chile, Camboida, East Timor, Rawanda, or Darfur, we exist in the eye of utter chaos; for most, it is difficult to do much more than stay alive. But those who are in the calm, watching the storm from the sidelines, are the only ones who can change the underlying system. There are many ways to do this, and inspiration can be found in amazing places. We may think that small acts cannot stand in the face of genocide, but ask someone who received bread over a barbed wire fence what that small act meant.

Recognize that potential for humanity in your everyday life of calm.

Thank you sir for this post. It’s been 13 years since I was there and it still looks the same in your pictures. I was with 100+ musicians and was one of the few stunned silent for most of the time I was there. My grandfather was there at the end of World War II as an american pilot and, at my request, told me some of what he saw but it is impossible to get the full feeling of dred that accompanies being there and seeing the triple bunk beds, the pictures of medical experiments, and sitting in that gas chamber.

You echo my thoughts and I apprecaite you putting words to them.

-Matt

And so we say as a people, “Never again.”