A few weeks ago I was at a trade show in Salt Lake City. I heard a presentation from the Director of Sustainability for Walmart. Yep, you heard right.

I’m glad they’re doing something. Given their gargantuan size, they can have a significant impact on the environment. They’re building stores with better efficiency and lighting. They’re buying land and putting it into conservation. They’re working on logistics to improve the efficiency of their 7,ooo truck fleet to get to a goal of 13 mpg by 2015 (which experts say is impossible, but at least they’re trying).

The problem is their definition of sustainability is focused on resources, not on people. It’s half-baked, so the center collapses.

There was no Q&A after the speech.

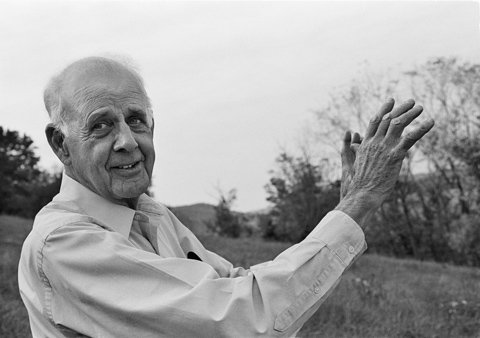

That brings me to my hero, Wendell.

Wendell Berry wrote these rules delineating how we ought to make decisions about changes, especially when it comes to the culture of our communities, towns, cities, and indeed, our whole country-as-community. I also believe they’re good guidelines to consider when making family decisions.

Let’s take a look. Please try to apply these questions honestly to yourself, your family and community. We are all hypocrites in one way or another. No judgement or self-flagellation; just think about it.

1. Always ask of any proposed change or innovation: What will this do to our community? How will this affect our common wealth.

2. Always include local nature – the land, the water, the air, the native creatures – within the membership of the community.

3. Always ask how local needs might be supplied from local sources, including the mutual help of neighbors.

4. Always supply local needs first (and only then think of exporting products – first to nearby cities, then to others).

5. Understand the ultimate unsoundness of the industrial doctrine of ‘labor saving’ if that implies poor work, unemployment, or any kind of pollution or contamination.

6. Develop properly scaled value-adding industries for local products to ensure that the community does not become merely a colony of national or global economy.

7. Develop small-scale industries and businesses to support the local farm and/or forest economy.

8. Strive to supply as much of the community’s own energy as possible.

9. Strive to increase earnings (in whatever form) within the community for as long as possible before they are paid out.

10. Make sure that money paid into the local economy circulates within the community and decrease expenditures outside the community.

11. Make the community able to invest in itself by maintaining its properties, keeping itself clean (without dirtying some other place), caring for its old people, and teaching its children.

12. See that the old and young take care of one another. The young must learn from the old, not necessarily, and not always in school. There must be no institutionalised childcare and no homes for the aged. The community knows and remembers itself by the association of old and young.

13. Account for costs now conventionally hidden or externalised. Whenever possible, these must be debited against monetary income.

14. Look into the possible uses of local currency, community-funded loan programs, systems of barter, and the like.

15. Always be aware of the economic value of neighborly acts. In our time, the costs of living are greatly increased by the loss of neighborhood, which leaves people to face their calamities alone.

16. A rural community should always be acquainted and interconnected with community-minded people in nearby towns and cities.

17. A sustainable rural economy will depend on urban consumers loyal to local products. Therefore, we are talking about an economy that will always be more cooperative than competitive.

So, how did you do?

I didn’t do so well. I have work to do. The most important thing that stuck out was my need to focus on how my buying patterns affect the whole community.

68 cents on the dollar spent in a local business stays in the community. A back of the envelope calculation of my own business says that this is pretty close to accurate. 42 cents on the dollar remain in the local community if you purchase at a chain store. That gap is the cash that flows to “the home office” like the one in Bentonville, Arkansas.

It may seem self-serving for a small, local, family-owned and operated business to promote buying local, but it goes far beyond that. A dollar kept in the community bounces around a lot…to the local co-op, where it is distributed as wages to their staff, who spend it at the local coffee shop, who use it to buy coffee from a local roaster, whose employees go back to buy food at the co-op. Yes, some bleeds out to external sources, but if we can keep just a few more bucks hanging around, what a difference it can make.

Respectfully submitted,

Canoelover

P.S. Spring is coming. so the posts on canoes and paddling stuff should appear more regularly. It’s hard to write about canoeing when there’s eight inches of snow on the ground, although it’s time for a winter paddle.